If you asked me what my favorite meat is, I’d answer immediately and with no qualifications

DUCK

Yet here in the USA, duck is often overlooked. It is considered a novelty – rarely bought and cooked.

But I’m on a one-woman mission to change that – duck is a treat, equal to the same love as a nice steak. And here’s why.

What is duck?

Ducks are waterfowl that have been domesticated over the generations by humans. While you can farm ducks for their down or eggs, the majority of duck husbandry is centered on meat production.

Duck is eaten in many cuisines worldwide – although it is especially predominant in Chinese cuisine (where over 75% of duck is consumed worldwide). It is also especially popular in Southeast Asian, Northeast Indian, and French cuisines.

While commonly consumed abroad, duck consumption in the USA is surprisingly low – only around .3 lbs per person a year (compare that to 60 lbs of beef per person!). There are several theories as to why it’s so low… Some say it is perceived as a delicacy due to its rarity, while others point to the higher price point stateside due the relative complexities of raising duck compared to chickens (for more on this look at my blog on duck eggs).

What does duck taste like?

Duck is a red-fleshed poultry that can often be found as a whole bird, in leg quarters (leg + thigh meat), or in breast cut.

Duck has a relatively high fat content (both in-meat, and under skin) and therefore is super rich in flavor. Some might call it a “gamier” bird, but I generally find it to be comparable to dark meat chicken when bought from the store (wild hunted duck is another story).

Red meat vs. white meat

According to the USDA, red meat is meat obtained from mammals and white meat is generally obtained from poultry and fish, but the terminology can get very mixed up in practical application.

Red meat gets its name from the high myoglobin levels in the meat, which make it red when raw. Once cooked it generally becomes a darker red or brown. Red meat is higher in saturated fat, but also contains a higher density of protein and iron.

White meat is pinkish when raw and white when cooked. It usually has less fat distributed throughout and therefore is less calorie dense and dries out more quickly when cooking.

Where this all gets confusing is when color doesn’t necessarily align with source. For example, lots of pork meat turns white when cooked, despite it coming from a mammal. So technically pork is a red meat, despite it looking like a white meat (and the successful 1980s advertising campaign letting us know it was the “other white meat”). Rabbit is also technically a red meat since it’s from a mammal, although it is low in fat, pink when raw and white when cooked (and cooks up INCREDIBLY similarly to chicken).

So where does duck fall in all of this? Duck is a bird, so according to the USDA it is a white meat. BUT, compared to all other poultry it has a significantly higher myoglobin count – which means it has a darker, red meat that stays red when cooked. So practically, it behaves much more like red meat when cooked.

All of that to say – duck may technically be a white meat, but you should be cooking it more like beef.

What temperature should you cook duck to?

So how much should you cook duck?

When I cook beef, I generally follow one of two methods – cook quickly to medium rare or cook a long time till it’s falling apart. And which method I use depends on which cut I’m cooking. A good steak should always be cooked to around medium rare – this temperature results in optimal tenderness and juiciness. But some cow muscles are exercised more and therefore contain more connective tissues. These shouldn’t be cooked medium rare – they’ll be too tough and hard to chew. These pieces need to be cooked a LONG TIME, until all that connective tissue breaks down and becomes tender.

Duck is the same way. Duck breast contains very little connective tissue and generally doesn’t see much exercise. So it handles being cooked to medium rare very well. This is enough cooking to render the THICK fat cap (which we’ll discuss more in depth later) but not too much to dry it out or make it tough.

On the other end of the spectrum, duck legs / things are much smaller than chicken thighs and contain a high level of connective tissue. If you only cooked them to medium rare you’d have a VERY CHEWY drumstick. However, if you cook duck legs a long time (till 165+), all the collagen and tissues break down into a tender and deeply rich meat. Just be careful not to let them dry out during that long cooking process. I’ll discuss (what is in my opinion) the ideal way to cook duck leg quarters later.

What about food safety?

Most people have heard the warning “don’t undercook chicken or you’ll get sick!”

And rightfully so. In the US over 1 MILLION people get sick from chicken-related foodborne illness every year.

One of the best and most consistent ways to prevent this is to cook your chicken to a temperature that is high enough – 165F according to the USDA. However, this is in direct opposition to my earlier statement that you should try to cook duck to medium rare (which is usually about 135F). So where does this discrepancy come from?

A lot of this comes down to processing. Chicken and ground beef processing are NOTORIOUS for their issues with cross-contamination here in the USA. It’s one of the main reasons that you should always cook chicken and ground beef all the way through.

But duck is not as widely commercially available and doesn’t have the same massive processing infrastructure. So the proverbial “jungle” of potential contamination is not as fraught. So many find the risk of contamination lower.

To be clear, eating medium rare duck is not advised by the USDA. But runny yolks and medium rare steaks are also considered no-nos. So consume at your own risk (but know that it’s a risk many chefs and home cooks – me included – opt to take).

Do note that if you have a sous vide you can technically pasteurize any poultry to achieve optimal internal temperature safely. Read this very well explained deep-dive if you want to learn more.

Duck vs. chicken

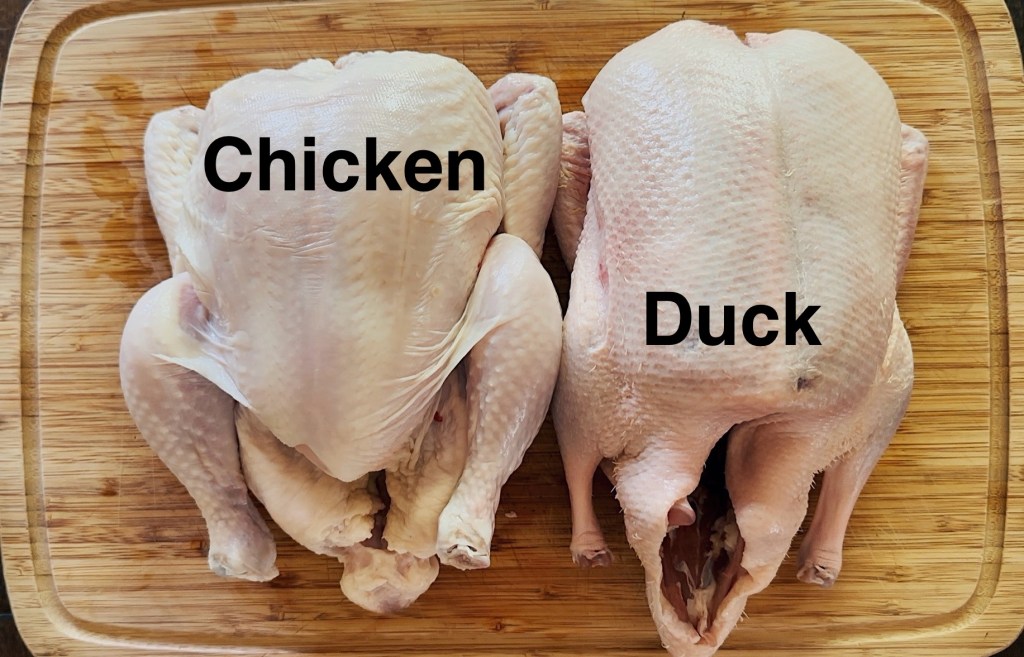

Since most eaters have had chicken before and both are birds, I find it useful to discuss duck in depth as compared to its more common cousin.

Duck is essentially a richer tasting chicken.

Duck is fattier than chicken, which means essentially all cuts will have more flavor. Ducks have both a thick fat cap under the skin and plenty of fat distributed throughout the meat. Duck is deeply savory and slightly more earthy than chicken, which has a very mild taste (this goes back to their diets – see my duck egg video for more details). Duck meat is also denser than chicken meat – duck meat have only 52% water, compared to 60% in chickens.

Anatomically, ducks are slightly larger than chickens. When bought whole at the store, you’ll often find chickens around 3-4 lbs, while whole ducks are often 4-6 lbs. Relative to their size, ducks have proportionally larger breasts and smaller thighs / legs. Duck breasts are also “flatter” than chicken breasts.

Duck fat

Even if you’ve never eaten duck, you may have come across “duck fat potatoes” or “duck fat fries” at a restaurant before. Why is that?

It all goes back to duck being a water bird.

Ducks have a thick layer of fat right underneath the skin. Like blubber in whales and seals, this layer of fat serves to help insulate ducks while in cool water and help them stay afloat. This fat can be fairly easily rendered (a culinary term for slowly heating meat to allow the fat to melt and separate from the flesh) and gathered to use in cooking.

When I roast a whole duck I can often gather almost a full jar of rendered duck fat, which when stored in the fridge can last up to 6 months (and almost indefinitely when kept frozen).

Where to buy it

Because duck is not one of the “Big Three” commercially produced meats in the USA, it is gonna be both trickier to find and more expensive.

As far as where to find it goes…

As a “specialty meat” you won’t often find it raw at the butchers department of most conventional grocery stores. I usually can find it in the frozen section of a grocery store, fresh at an Asian grocery store, or at the Farmer’s Market (although you may still need to ask around about who to buy it from).

Why is duck so expensive?

If you’ve read my duck egg blog, you’ll know that ducks are hard to commercially raise. They need access to water and more space than chickens, so fewer people try to produce them. Interestingly, back when it was more common to sell hunted meat duck was WAY more popular. The decline in sales didn’t really hit until the industrialization of the meat industry in the 19th century.

These days, duck is generally raised on smaller farms where living standards are generally better, but also expenses are higher. Duck will never be as cheap as chicken because of this.

BUT… duck has a lower carbon footprint AND cheaper price than what I consider its closest competitor – beef steak.

So while duck will never replace conventional chicken, I would argue that it should take some of steaks market share.

How to cook duck

While duck may look superficially a lot like chicken, it is cooked in a fundamentally different way. If you try to just substitute cuts of duck for chicken in most recipes, it’s not gonna go well. A lot of this is due to the thick fat layer on ducks.

The fat on ducks gives it its incredible taste BUT when not cooked properly turns this delicacy into a greasy mess. Your primary goal when cooking duck should be to render the fat while properly cooking the meat.

Rendering duck fat

Duck fat provides flavor and moisture to the meat, but if left intact will be rubbery, greasy, and unpleasant to eat. Every time you cook duck you need to ask “how am I going to melt the fat”?

Regardless of other cooking method, you should generally try to start cooking duck (and any meat tbh) at room temperature. Letting meat slightly heat (or just not be cold) will allow it to cook more evenly. It also allows the fat – which we are trying to melt – to start off the cooking process closer to its melting point.

When looking at your cut of meat, you should be able to see where the thick layer of fat is. Regardless of cooking method, you should start by gently adding some slices to the fat cap, but be careful not to cut the meat! Adding “grooves” through the fat layer give it more places to melt from, increasing the melting speed – just think about how fast crushed ice will melt compared to one large block.

One more thing to consider with duck fat is whether or not you’d like to save it once it’s rendered. If you plan to drain it and store it in the fridge, consider (regardless of recipe) beginning your cooking with minimal seasonings. I often start the duck with just salt and pepper, then once I’ve gathered the melted fat I add any other distinct flavors. This ensures that my jar of fat has as few extra things / flavors as possible.

Cooking with duck fat

Duck fat is kind of like liquid gold.

There’s a huge trend these days to get “duck fat potatoes” – and while maybe mildly overdone – it’s for a good reason. Duck fat is rich, earthy, and has a deep umami flavor.

I love to fold duck fat instead of (or in addition to, let’s be honest) butter in mashed potatoes – especially when they’re served with duck! I also often use duck fat when roasting veggies to take them up a notch.

Like most animal fats, duck fat has a relatively high smoke (375F). This means it can handle high-heat cooking methods like sautéing and roasting without burning and breaking down into bitter-tasting compounds.

All this to say… When you cook duck, save the fat. And use the fat.

Duck breast

The way you cook duck STRONGLY depends on what cut you’re using, so we’re gonna go through each separately, starting with duck breast.

Duck breast is very similar to steak or skin-on salmon in how you cook it.

The final goal is medium rare (although you can go to 165F if you’re more risk-averse – just make a sauce).

Here’s a fairly easy method for pan-searing duck breast (although duck confit is, in my opinion, the best way to cook duck breast – it’s just a bit more labor intensive)

Once you cut the fat, as mentioned above, go ahead and heat a pan over medium heat with a little oil (you don’t need much oil, since a bunch of fat is gonna render into the pan shortly).

You’re gonna want to cook the duck 90% of the way on the skin side – this ensures all the fat renders before the meat can overcook. When most of fat has seeped out and the skin is a deep golden-brown, flip it over and cook the other side just till there’s color.

At this point the internal temp should be about 130F – it should rise to 135F (medium rare) while resting – so go ahead and take it out of the pan and let it rest. Be sure to set it skin-side UP so that crispy skin doesn’t go soggy. Slice against the grain and enjoy!

Duck leg quarters

As we noted before, duck legs are smaller relative to their body size than chicken legs. This means you’ll rarely find just duck legs for sale – more often than not you’ll find duck leg quarters, which are the leg and thigh combined.

As dark meat on an already very fatty bird, duck leg quarters are VERY dappled in fat and can withstand a LOT of cooking. I consider them similar to a tough beef cut – cooking it low and slow will make it tender, allow the fat to render, and the skin to crisp. I generally advise cooking them to AT LEAST 165F, which is well done for a bird.

I always recommend starting with this cut your first time cooking duck. In fact, here’s my…

Foolproof duck leg quarter recipe

It’s really simple to cook WONDERFUL duck leg quarters. And when you do it right, you’ll also end up with a decent amount of duck fat leftover to use for other dishes.

Here’s the process..

- Preheat oven to 325F

- Rinse off your duck leg quarters and pat them dry

- Take a knife and gently slice a grid into the duck fat, being careful not to slice the meat itself

- Liberally salt and pepper the skin (avoid other seasonings for now – you want the rendered fat to be free of extra flavors)

- Tuck the quarters into a small baking dish – just big enough to fit the meat with little extra space

- Place into the oven

- Roast leg quarters for about 1.5 hours, until almost all the fat has seeped out of the skin (they’ll almost be “swimming” in rendered fat)

- Take the baking dish out of the oven and raise the temp to 375F

- Remove the duck pieces from the baking dish and let them rest for a minute on a cutting board

- Drain all the rendered fat into a jar – you can use this for other recipes

- Move duck back to the empty baking dish

- Now you can season the duck to your liking, making sure there enough liquid to lightly cover the bottom of the pan

- Return the duck to the oven and roast until the top is golden brown and very crispy – usually an additional 40 minutes (but this may vary based on the meat size and your oven)

- Let the duck rest for at least 10 minutes before serving, drizzling marinade from pan on top

It’s such a simple method. It does take a while, but there’s very little “active cooking”. And duck thighs are essentially impossible to overcook (like chicken thighs), so there’s a lot of wiggle room.

As far as marinades for the duck go, orange and duck are a popular combo. But I prefer the following for 2 leg quarters (increase the amounts for more duck accordingly)…

- 1-2 tbsp of the reserved duck fat

- 1 tbsp soy

- 1 tbsp fish sauce

- 2 tbsp balsamic vinegar

- 1/2 tsp mustard powder

- 1 tbsp honey

Simply whisk these together in a small bowl and pour over the leg quarters (after draining the fat) before the second roast.

Enjoy!

Cooking a whole duck

Roasting a whole duck is a bit of a balance. As we noted above, duck breast should be cooked medium rare, but the dark meat needs to be cooked much more. So how do you do both?

You don’t.

You’re likely gonna end up “overcooking” your breast meat to make sure the thigh meat is tender. And that’s okay. Just try to use a well-established recipe, and you’ll likely end up with crispy skin and not-overly-dry white meat. Here’s a recipe I’ll often use.

Closing remarks

Duck is a protein that is a perfect balance of familiar and adventurous. It’s somehow similar to both chicken and steak, and makes some of the most decadent, delightful meals – without breaking the bank the way some steaks might.

If you’ve never had duck before, please go try it at a restaurant! Or make it for yourself. While not exactly the same as chicken, it really isn’t more complicated to make. And you may find yourself with a new favorite protein – or at least a new “fancy bird” this Thanksgiving.

And if you do, come share your favorite recipe here.

Happy eating!

Do you like educational food content, but prefer a video format? Check out the video form of this blog on our socials…